It’s a frequent lament now how the “hot take” has subsumed and redefined contemporary cultural criticism, with music criticism being perhaps the most egregiously affected. (A strong argument could be made that film criticism and commentary are just as fucked up.) A music artist drops a new project at noon and by 2 PM social media and Youtube are flooded with reviews of it by nu-school “critics.” Most mainstream media outlets will drop their reviews online within 1-3 business days, which ain’t always much better. Social media’s demand for a nonstop flow of content, and the voracious appetite of a public conditioned to receive and give immediate responses to everything (no matter how ill-informed that response might be,) are rightly blamed, but the roots of it all stretch back to pre-social media days (or at least before social media was the toxic Goliath it now is,) to record industry fears of piracy.

Back in the early-mid aughts I freelanced quite a bit for Rolling Stone, and one day got a call from an editor asking if I was interested in reviewing the new Meshell Ndegeocello album. I was and remain a huge, huge fan and had interviewed her twice by this point so I leapt at the chance. “Great,” he replied, “I’ll have her label messenger over the advance. You’ll have it by this evening or first thing tomorrow morning. It’s due Wednesday by 9 AM sharp.”

Que?

It was already mid-afternoon Monday. For a lot of young music writers today that will seem more than enough time to crank out some content. But while the time afforded critics to file reviews after listening to an advance CD (a.k.a. a review copy) had been shrinking for a while by the time I got that assignment, I’d not yet experienced such a narrow window of time to turn around an album review. There was a time [let me break out my old man rocking chair] when you’d receive an advance CD weeks (if not a couple of months) ahead of the music arriving in stores. (There were and always had been exceptions to that extended time frame, for a host of reasons.) You got to sit with the music, luxuriate in it, slowly peel away layers, consider and reconsider your visceral reaction versus your time-release feelings. You got to juggle various angles of critical thought as you contextualized and historicized the music. And you had time to find your way in if no door was open.

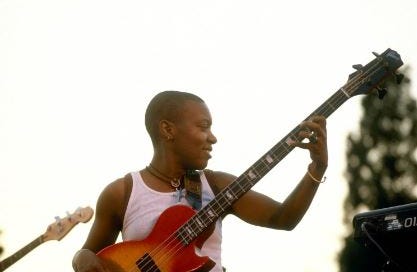

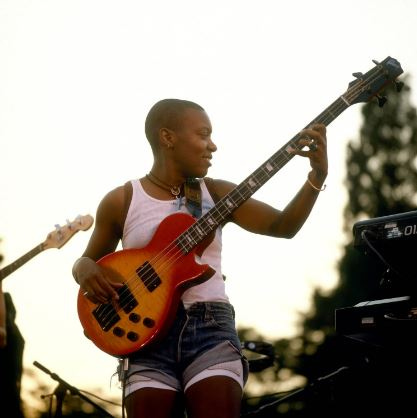

This clip above? Eleven minutes of pure fire…

The rise of Napster (the poacher who milked the music industry’s cash cow) changed all that. It meant that shortly after advances were sent out (sometimes mere hours) they’d be available online through file sharing. Labels coded CDs with watermarks or anti-copying technology but it wasn’t enough to stem the tide of high-tech bootlegging, which meant critics started receiving music five minutes before it dropped in record stores in the labels’ efforts to get ahead of lost sales and revenue. That’s an exaggeration but only just, and gives some idea of how tight the time crunch was. The new system wasn’t perfect and was inconsistently applied. A lot depended on how far up the food chain you and/or your publication were, and how big the music artist was. In some cases you had to travel to label offices where they’d place you in an empty conference room and play the music for you. You’d be given a set amount of time or number of listens during which to take your notes.

Fed-Ex brought the CD the next morning and I listened to it all day. At the time it was a big departure from what I expected, what I thought I knew of Meshell. Despite how vast I knew her talent was, I’d still placed her in a box my ears couldn’t hear beyond. I gave the CD a lukewarm review and kept it moving. Only, I couldn’t quite shake it. I kept making my way back to it, each time falling deeper under its spell. I listened to it while washing dishes, eating dinner, sprawled across my bed staring at the ceiling, while [redacted] – which is really what did the trick. I ended up going to John Payne, then the music editor at the LA Weekly (and one of the most chill humans ever,) and telling him my Rolling Stone review had missed by a mile, and I wanted to write a new review in which I admitted my fuck up and instead sang the album’s praises. He loved the idea and let me write that piece.

Since that album (which I will not name since it’s so clearly a masterpiece I’m embarrassed to have shortchanged it) there have been one or two other Meshell albums that took a minute to unveil their charms to me (and two or three that ensnared me immediately,) but I knew to be patient. Sometimes it takes a shift in your head-space or heart-space for a piece of art to speak to you – same art, different internal context, and the epiphanies flow.

With No More Water: The Gospel of James Baldwin, Meshell’s Grammy-winning, critically acclaimed collaboration with/channeling of the work and spirit of James Baldwin, I immediately had enormous respect for it but it didn’t hit me the way it hit so many others, despite repeated listening. Two friends in different parts of the country went to live performances of it and raved. One told me she wept throughout the concert. I get that now.

Watching the concert performance below broke No More Water wide open for me. What most impresses me is the fusion of genius it captures, and how difficult a feat that is to pull off. It makes me think of when an actor portrays a well-known real life figure and they do all the research, read letters, listen to recordings, watch film clips and news reels, master the mannerisms and tics, and yet have to figure out a way to bring their interpretive skills to play so it’s both artistically satisfying for them and more than mere mimicry for the audience (some of whom will want mere mimicry.)

Swim through the bodies of work of Baldwin and Meshell and its clear each was on a spiritual quest from the start of their careers, trying to make sense of the workings of the world, trying to distill beauty and meaning from life with their social commentary, political analysis, and surgical precision in dissecting how our romantic/personal lives can be both dumping grounds for trauma and vessels of possible transcendence (even if that transcendence is fleeting and not always a dependable counter-force to the ills of the world.) With Meshell that quest was pointedly but poetically spelled out on her 1996 sophomore album Peace Beyond Passion, but listening to her 1993 debut album Plantation Lullabies in the context of her body of work makes clear that that classic R&B/hip-hop/funk/jazz/go-go inflected offering was first and always about Spirit. Like with Stevie. Like with Marvin. Like with Prince. Like with Miss Nina.

The great musicians (which includes vocalists) teach us how to listen – Miles, Billie, Sarah, Monk, Meshell… Sometimes it requires stillness on our part. Sometimes it demands hella active listening. Sometimes it requires introducing yourself to the music they offer by stripping away everything you think you already know about them. Start anew.

Meshell accepting the Grammy for No More Water…

Below is a different performance of “Trouble” than the one that’s part of the concert above. It’s a haunting meditation, a cleansing ritual and prayer, from the fused being of Baldwin/Meshell (& crew) in which they speak to just this very moment we’re in.

What's another word for trouble? 'Cause that's what we're in

Everyone's down for the struggle until it begins

Pain makes you humble, hurt is hard to sing

What's another word for trouble?

1) I miss those kinds of long, considered reviews (another way of saying I miss The Village Voice and various alt-weeklys)

2) As our North Star (Samuel R. Delany) wrote somewhere, Some books teach you how to read them. The artists you mention above are the same: their work teaches you how to listen in general, and to them specifically.